The year 2019 in infectious disease was one of near-misses, close calls and emerging threats. The United States narrowly avoided losing its measles elimination status in 2019 thanks to a series of outbreaks in antivax enclaves. Meanwhile, ebola virus continued to run rampant in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in an outbreak that began in 2018 and shows no signs of stopping. Finally, an uptick in cases of a rare but serious mosquito-borne infection has experts worried for the future.

Here are the top three infectious disease stories of 2019.

The Most Measles Cases in 20 Years

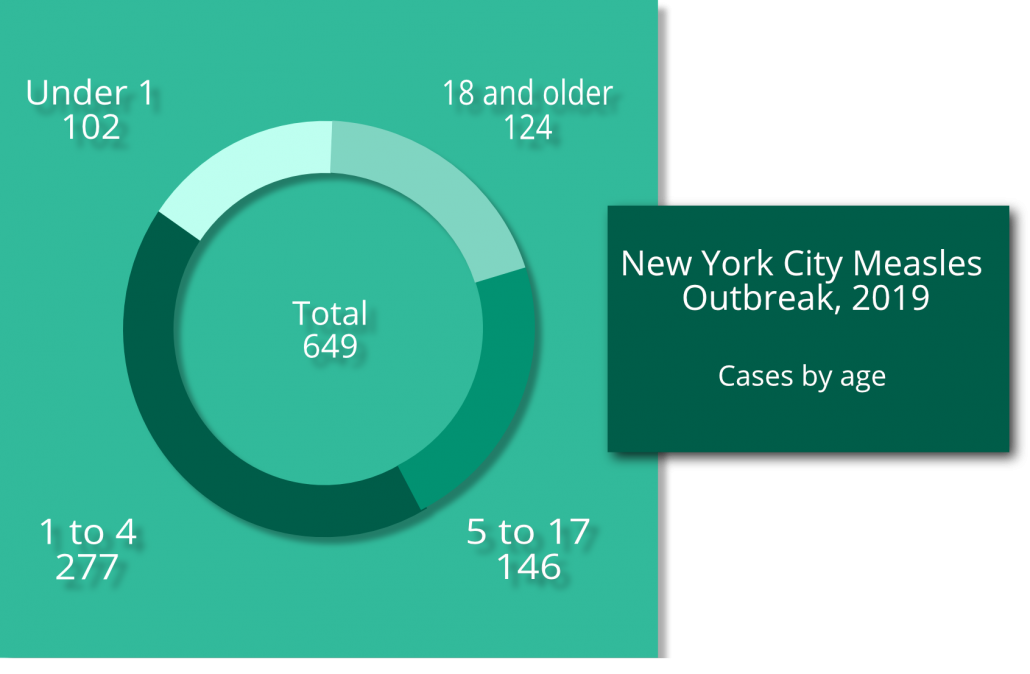

Large outbreaks in undervaccinated communities gave 2019 the most measles cases in the United States since the disease was eliminated in 2000. On the year there were 1,282 cases. A New York City outbreaks in two Brooklyn neighborhoods accounted for 649—more than half—of those cases before city health authorities declared the outbreak over in early September.

Unvaccinated travelers are vulnerable to measles exposure in places where it still exists in the wild. They expose others when they return to their communities. In areas with high vaccine coverage, herd immunity protects most people and contains outbreaks.

But Williamsburg and Borough Park, the two Brooklyn neighborhoods most affected by the New York City measles outbreak, are dominated by those who follow a sect of Judaism that religiously opposes vaccination. Measles can run rampant through undervaccinated communities, and in this outbreak children under five were the vast majority of those sick.

The measles mumps rubella vaccine schedule calls for the first dose at 12 to 15 months of age and another at age 4 to 6. It’s not necessarily surprising that 102 infants under 1 fell ill, but even one vaccine greatly decreased the risk of contracting measles. Of the 277 cases in children ages 1 to 4, only 32 were in kids who had their first dose of MMR vaccine.

Worldwide, there were more than 440,000 measles cases. The World Health Organization warns that communities with less than a 95 percent vaccine rate are vulnerable to outbreaks. Don’t let antivax propaganda mislead you—vaccines are safe and effective.

Ebola Still Spreading Through DRC

The second-largest Ebola virus outbreak in history, which started in 2018, continued to rage through the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) last year, with no signs of stopping in early 2020. As of January 16, there have been more than 3,400 cases. The mortality rate for this outbreak is 66 percent—higher than the 50 percent average.

Ebola spreads from person to person via contact with blood or bodily fluids. Vomiting and diarrhea are two of the virus’s main symptoms, which makes the virus highly contagious.

Development of an Ebola vaccine kicked off during the last major outbreak, which happened in 2015 through 2016 and was the largest in history. By November of 2019, about 250,000 people had been given the Ebola vaccine. A second experimental vaccine also hit the ground in the DRC in November, about 11,000 doses.

Despite the first vaccine’s availability and efficacy—trials put it at 97.5 percent effective—prolonged civil unrest and violence in the DRC, vaccine refusal, insufficient rural healthcare and delayed healthcare seeking make responding to the outbreak a challenge. DRC is still seeing new cases as of late January.

Eastern Equine Encephalitis Cases Spike in 2019

Any more than a handful of reported cases of Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) in a year is bound to ping the radar of anyone monitoring. Between 2009 and 2018, people reported an average of only seven cases per year. There were almost 40 reported cases and 15 deaths in 2019.

Still, 40 cases? Out of 320 million Americans? That’s not that much…for now. Writing in New England Journal of Medicine, officials from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) urge vigilance and note our unpreparedness for dealing with EEE and other mosquito- and tick-borne arboviruses.

EEE is usually isolated within Culiseta melanura mosquitoes and tree-dwelling birds such as the American robin. Other mosquitos sometimes transmit the virus to humans. The NIAID officials point out that other arboviruses—dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya and Zika—have all evolved for transmission by the A. aegyptis mosquito, one of humankind’s most voracious predators. That’s exactly why they’re some of the most widespread diseases in the world.

EEE and A. aegyptis teaming up would be bad news. Although only 4 percent of those infected show symptoms (that means there were probably about 1,000 cases total in 2019), a third or more of those cases are fatal and most of the rest suffer permanent brain damage.

There’s currently no vaccine and no effective treatments for EEE. Any medication would have to cross the blood-brain barrier, which makes developing treatments a challenge. Oh, and the NEJM article points out EEE’s potential to be weaponized.

Do Your Part

Many viral infections, including measles, rely on vaccines and herd immunity to protect public health. Do your part to protect yourself, your family and the most vulnerable members of your community by following all scientifically optimized vaccination schedules. You can also keep tabs on infectious disease monitoring efforts by following the CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System.

Are you part of the next generation of healthcare providers? Brush up on your viral infection diagnosis with our beautiful, full-color Virus Classification Flowchart poster. You can collect all 20 of our Curative Design poster series, perfect for a dorm room—or an exam room.